Details of Indigenous Find Reveals Lack of Engagement with Local First Nations

Joshua Read, Stantec archeologist, presents his findings of a Medicine Hat excavation in August 2023 at the construction site at the city’s water treatment plant during the Archeological Society of Alberta’s AGM held at Medalta at the end of April. (Photo Alex McCuaig)

A stitching awl used to pierce hides and leather may not be an object of any particular fascination. But when it’s well over a thousand years old, handmade from a bison’s rib by the First Peoples of Medicine Hat and recovered from underneath metres of earth, there’s a story to be told.

For Brenda Mercer, whose journey to reconnect with her Indigenous past is in part through sharing traditional crafts, the find of such an item clearly resonates.

It’s far murkier the reasons for not allowing Mercer or other members of the local Indigenous community access to the discovery or why city officials denied to even inform them of a pre-Columbian discovery.

Mercer is now hoping the city can retrieve some of the items removed from the Hat.

“Truth and Reconciliation is so important right now and let’s put some action into these words today and let’s get some pieces back here,” said Mercer. “Three little pieces at the start. That’s all we’re asking for.”

An awl made from the rib bone of a bison recovered from an excavation at the Medicine Hat water treatment plant. (Photo courtesy of Stantec)

An eight-month investigation into the discovery of an Indigenous site during construction of a city project launched by the Medicine Hat Owl has uncovered information questioning the municipal government’s commitment to “honor and respect” First Nations’ connections to the land.

Starting in August 2024 and after receiving numerous tips regarding a significant find at the construction site for a new building at the water treatment facility, the Owl began asking details regarding the discovery.

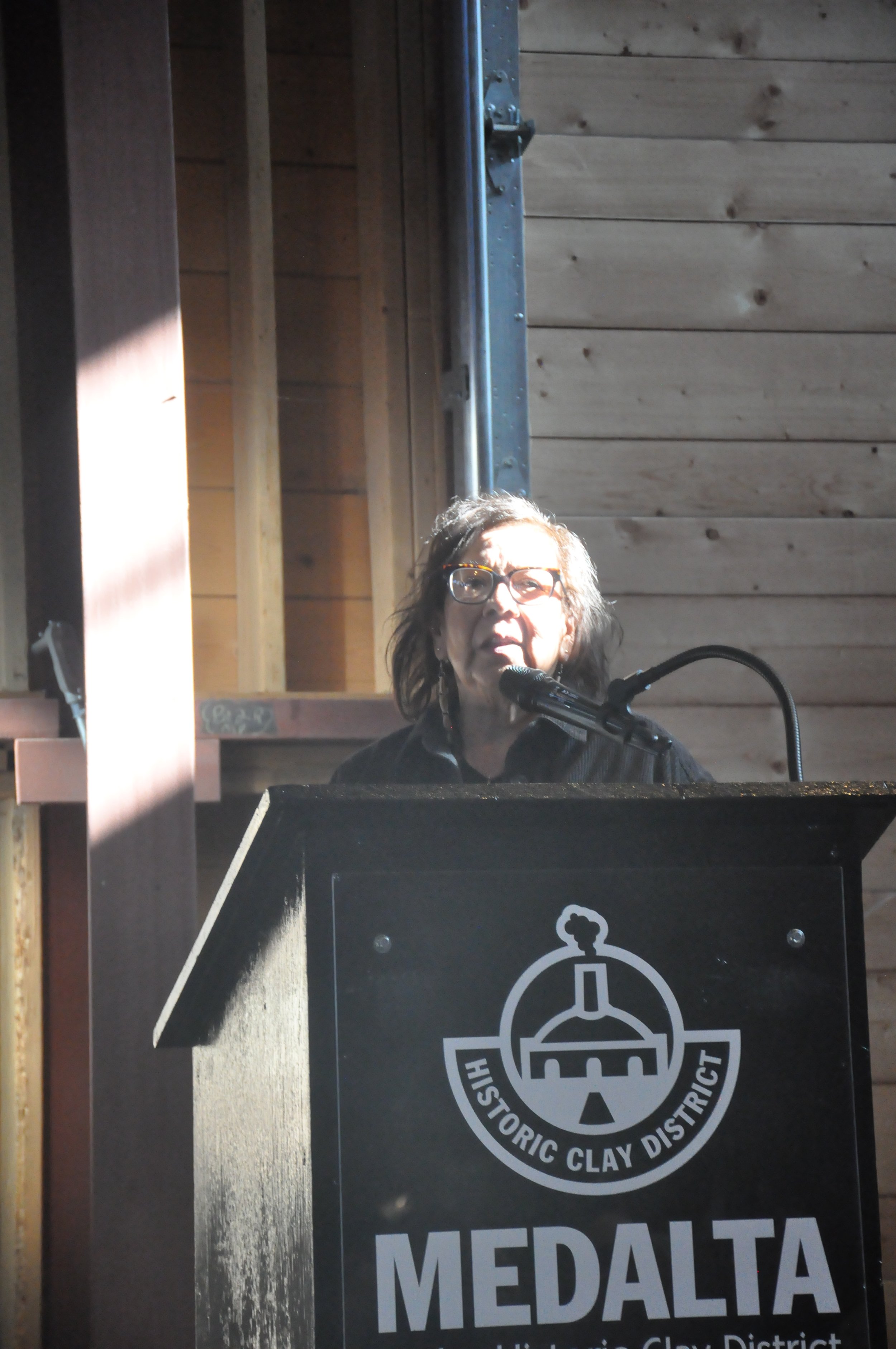

Brenda Mercer addresses the Archeological Society of Alberta’s AGM in late April. (Photo Alex McCuaig)

The Owl’s investigation culminated following a presentation by Stantec, the contractor that city administration hired to do the excavation, at the Archeological Society of Alberta’s AGM held at Medalta in late April This despite elected and administrative officials stating the province had directed them to not disclose details about the excavation.

The discovery was made in June 2023 followed by a two-week excavation that was completed in mid-August with work allowed to continue approximately one month later.

The report details how the initial discovery of evidence of a lightly-use site at a depth of 2.5 metres led archeologist to look deeper.

At four metres, they found evidence of a heavily used secondary meat processing site, primarily utilized for bison but also deer and pronghorn. A hearth was uncovered along with tools and spearpoints dating to over 1,500 years ago.

Thousands of items were found at the site and, according to the report and, “resulted in the recovery of a robust artifact assemblage and the identification of two distinct cultural occupations.

“Not only has this work provided data for future research but it highlights the need for a reassessment of standards regarding pre-impact archaeological investigations in the Medicine Hat area, particularly along the South Saskatchewan River terraces.”

Despite the significance of the find, inquiries by members of the local Indigenous and archeology communities for details of the 2023 discovery were rebuffed.

The city and ministry responsible for archeological finds, Arts, Culture and Status of Women, as well as the constituency offices of the city’s two MLAs, Premier Danielle Smith and Justin Wright, stated the threat of looting was a concern.

According to the report and presentation by Stantec archeologist Josh Read, the significant portions of the find were located four metres underground, requiring the deft operation of an experienced excavator operator. The site was also within an active construction site area enclosed by an approximately eight-foot-high fence topped with barbed-wire.

“Archaeological site information is made readily available to archaeologists and Indigenous communities in Alberta,” Smith’s constituency office stated, “but broader distribution is typically restricted to prevent unauthorized disturbances and looting.”

Provincial officials deny any direction was given to the city to not to release information regarding the find. But an email obtained by the Owl from the provincial director of the Archeological Survey, Darryl Bereziuk, directed all communication go through the government of Alberta.

Despite that, Juliana Rodriguez, spokesperson with the ministry of culture, stated that when it comes to the city not disclosing information about the site that, “there is no part of the policy or process - or any part of the Historical Resource Act - that gives this direction.”

In a January 2024 request for a budget amendment for the water treatment facility, city staff told council the excavation delayed the project by six months. The Stantec report outlined a three-month timeline from discovery to the green light from the province to continue work.

Stantec was already onsite at the onset of construction with a paleontologist as there was a possibility of discovery of fossils.

Broken projectile points (EaOq-82:6811, 6813, 7219, 7223), Samantha/Avonlea arrow points (EaOq-82:7221, 7222) and a Besant dart point (EaOq-82:7224) recovered from the excavation site at the city’s water treatment facility. (Photo courtesy of Stantec)

Read also told the Owl that informing and having members of the local Indigenous community has value during archeological discoveries.

“One hundred percent,” said Read during an interview following his presentation. “I’ve worked on plenty of projects where we’ve had either Indigenous monitors or Indigenous participants. . .I’ve worked on many projects where we’ve had Indigenous groups come out and do a blessing before a project starts at a site.”

While Read said he wasn’t involved in the decision making which prevented local Indigenous participation in the excavation, the value of their presence is clear.

“There is really valuable work to be done in engaging with and collaborating with various Indigenous communities because this is – for the most part – a lot of what we do as archologists in the province – excavating and investigating Indigenous history,” he said.

Brian Vivian, president of the Archeological Society of Alberta, also stressed the importance of involvement of Indigenous communities in archeological digs and there are no barriers to their participation.

“Historic resources are owned by the people of Alberta. Anybody is open and able to participate in access to those,” said Vivian to the Owl.

He added that there are limitations of who can oversee such archeological excavations, which require certifications from province.

That includes not just First Nations participants but community volunteers.

Vivian agreed there is a moral responsibility to allow Indigenous communities access to sites reflective of the tangible connections of First Nations to the land.

“I’ve worked on projects where I’ve taken steps to bring in First Nations people to do blessings on sites, be full participants in excavations and things of that sort,” said Vivian. “We have to do a better job reaching out to making sure reconciliation – the other side of the equation, the First Nations side – is recognized, that we’re reaching out to them and asking them for their input into sites as well.”

But city and provincial officials appear to view the issue differently.

On May 1, days following Stantec’s presentation, city officials stated they had been cleared by the province to release the report its contractor had completed and already presented publicly.

Some of the thousands of bones found at the site of an up to 1,500-year-old Indigenous meat processing site. (Photo courtesy of Stantec)

“From (the director of Archaeological Survey’s) review, they determined that sharing this (sic) results of the assessment poses little risk of disturbance to the site, and that we are now able to disclose the information,” stated Terra Petryshyn, city administration spokesperson.

But up to the point of the public release of the report, city council also appeared to be unaware of the nature of the archeological find as well.

The only two councillors who responded to repeated questions regarding the discovery, Mayor Linnsie Clark and Coun. Alison Van Dyke, told the Owl they couldn’t comment because the information hadn’t been shared with them.

Following the public release of the Stantec report, Clark didn’t respond to an interview request while Van Dyke did.

“I repeatedly stated that I could not comment on a report I had not seen and that the Province had requested we not discuss,” stated Van Dyke in a May 8 email seeking any additional information she’d like to contribute following the report’s public release.

A subsequent email from city manager Ann Mitchell stated council had been provided a copy of the report.

Clark was the only member of city council at the Stantec presentation but was not available for comment at the time.

City police inspect a pile of bones uncovered last summer during construction at the intersection of Third Street and Sixth Avenue. (File photo)

City officials not only didn’t provide an opportunity for the local Indigenous community access to the site, but they also wouldn’t publicly acknowledge the discovery of archeologic find at the water treatment plant was Indigenous in nature until its contractor did.

Starting in August 2024 – nearly a year following completion of the excavation and six-months following submission to provincial officials of Stantec’s report, the city’s position was it was the province’s call to release information pertaining to the excavation.

In an August 2024 email reply to questions about the site, Darryl Bereziuk, director of the Archeological Survey, stated there is sometimes overlap between what the province determines is archaeological sites and Indigenous traditional use sites of an historic nature.

“In this instance, the archaeological site in question has not been flagged to our department by local communities as a site of interest associated with modern or historic traditional uses,” stated Bereziuk. “So, it is regulated and managed solely as an archaeological site.”

According to a bulletin issued by the provincial government in February 2024, if an Indigenous traditional use site could be adversely impacted by a development, “the developer will be required to notify Indigenous communities affiliated with the site of the proposed development activities and their potential effect on the site.”

Despite the Stantec report indicated the excavation uncovered a more than 1,500 old Indigenous bison processing camp, it likely a small part of a larger site and its provincial archeological rating noting it is cultural in nature, the local Indigenous community wasn’t notified about its existence.

While a land acknowledgement at the beginning of each city council meeting pledges to honour and respect the past, present and future of Indigenous peoples, its track record is far from enviable.

The past has seen the municipality bulldoze a 5,000-year-old Indigenous site such as that discovered in Ross Glen as well as other pre-contact locations in South Ridge and Ranchlands. The present, represented by the water treatment facility find and lack of involvement of the Indigenous community, is indicative of the municipality’s current view. The combination raises questions of the municipality’s pledge to honour and respect ties of First Nations to the land in the future.

An August 2024 inquiry to the city regarding whether Medicine Hat has any municipal policy regarding finds involving Indigenous archeological finds, city administration spokesperson Petryshyn said there wasn’t.

“A policy would otherwise be redundant in repeating what the province requires of us. Rather, the City assesses potential expectations for HRV items as part of our internal technical coordinating committee screening process before advancing new work of this nature,” she stated in an email.

A follow up question regarding the same question regarding such a policy, city public services director Joe Hutter soften that stance in a statement earlier this month.

“We are continually seeking ways to improve how the City demonstrates reconciliation and may consider exploring the potential benefits of such a policy in the future,” stated Hutter.

But when asked if a find of the nature of the one discovered at the water treatment plant would be treated the same when it comes to notifying local Indigenous groups, Hutter didn’t respond.

Of the current listings of the 81 municipal historic resources, none are pre-contact Indigenous sites. Saratoga Park was added to the list in 2020, with the site being identified as a post-contact settlement for the local Metis and Indigenous communities.

The plaque and story board unveiled following designation of Saratoga Park as a municipal historic resource in 2020. (File photo)

The other 80 municipal historic sites range from homes, the Cypress Club and a civil defence siren from the 1960s.

Hutter stated either city council or its Historic Resource Working Group can designate Indigenous sites as municipally recognized sites. Despite that ability, the city hasn’t recognized any of the currently know pre-contact sites within Medicine Hat boundaries.

The municipality, however, is engaged in reconciliation efforts.

Following a 2017 request by a member of the public regarding repatriating Indigenous remains removed during archeological excavations in the 1960s by the University of Alberta, the city launched its Ancestors Reburial Project in 2023.

Those remains were unearthed in 1967 following badger activity on private land and excavated by University of Alberta archeologists who were in the area on another dig.

Above and below are pictures from 1935 of some of the gravesites which made up what was known as the “Indian Cemetery.” The fencing at the site eventually fell into disrepair. (Photos courtesy of Esplanade Archives)

A repatriation ceremony scheduled for last fall was postponed. However, the city has identified the Hillside Cemetery as the location of internment.

“The Team continues to consult directly with Indigenous Nations and communities, with various meetings and activities scheduled this month,” stated Hutter in an emailed statement. “As more Nations and communities’ express interest in the reburial, the project team is taking time to appropriately engage with interested parties individually and collectively to see this important work advanced in a good way.”

Mercer said she would like the city to develop a policy to follow when it comes to Indigenous sites in the city.

“I think it would have been nice if somebody would notify Miywasin or some Indigenous person in the community so maybe we can be there as they are (excavating),” she said. “Maybe not everybody but an elder, for example, might want to be there and watch.”

As for Mercer, such discoveries – like those found at the water treatment plant – represent an important trait of the Indigenous people who occupied Medicine Hat before European settlement.

“Resiliency.”

*The original article has been corrected to reflect the location of the recovery of the remains that are part of the Ancestors Reburial Project.